in what industries would you expect to see efficiency wages?

Chapter 10. Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

10.1 Monopolistic Competition

Learning Objectives

By the finish of this section, you lot will be able to:

- Explicate the significance of differentiated products

- Describe how a monopolistic competitor chooses price and quantity

- Discuss entry, get out, and efficiency as they pertain to monopolistic competition

- Analyze how advertizement can touch on monopolistic competition

Monopolistic competition involves many firms competing against each other, only selling products that are distinctive in some way. Examples include stores that sell different styles of clothing; restaurants or grocery stores that sell different kinds of food; and fifty-fifty products like golf balls or beer that may be at least somewhat like only differ in public perception because of advertisement and make names. There are over 600,000 restaurants in the Us. When products are distinctive, each business firm has a mini-monopoly on its particular style or flavour or make name. Still, firms producing such products must also compete with other styles and flavors and brand names. The term "monopolistic contest" captures this mixture of mini-monopoly and tough competition, and the post-obit Articulate It Up feature introduces its derivation.

Who invented the theory of imperfect competition?

The theory of imperfect competition was developed by two economists independently simply simultaneously in 1933. The outset was Edward Chamberlin of Harvard University who published The Economics of Monopolistic Competition. The second was Joan Robinson of Cambridge Academy who published The Economics of Imperfect Competition. Robinson subsequently became interested in macroeconomics where she became a prominent Keynesian, and later a post-Keynesian economist. (See the Welcome to Economics! and The Keynesian Perspective chapters for more on Keynes.)

Differentiated Products

A firm can try to make its products different from those of its competitors in several ways: physical aspects of the product, location from which the product is sold, intangible aspects of the product, and perceptions of the production. Products that are distinctive in one of these ways are called differentiated products.

Physical aspects of a product include all the phrases you hear in advertisements: unbreakable bottle, nonstick surface, freezer-to-microwave, non-shrink, extra spicy, newly redesigned for your comfort. The location of a house tin can also create a deviation between producers. For example, a gas station located at a heavily traveled intersection can probably sell more gas, because more cars bulldoze by that corner. A supplier to an automobile manufacturer may find that it is an advantage to locate close to the car factory.

Intangible aspects can differentiate a product, too. Some intangible aspects may be promises like a guarantee of satisfaction or money back, a reputation for high quality, services like free delivery, or offering a loan to purchase the product. Finally, product differentiation may occur in the minds of buyers. For example, many people could not tell the divergence in taste between common varieties of beer or cigarettes if they were blindfolded but, because of by habits and advertizement, they accept potent preferences for certain brands. Advertising can play a office in shaping these intangible preferences.

The concept of differentiated products is closely related to the degree of multifariousness that is bachelor. If everyone in the economy wore only blue jeans, ate only white bread, and drank only tap h2o, then the markets for wearable, nutrient, and drink would exist much closer to perfectly competitive. The variety of styles, flavors, locations, and characteristics creates product differentiation and monopolistic competition.

Perceived Demand for a Monopolistic Competitor

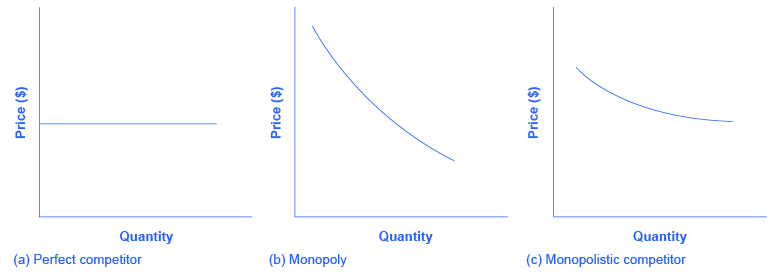

A monopolistically competitive house perceives a demand for its goods that is an intermediate case betwixt monopoly and competition. Figure 1 offers a reminder that the demand curve every bit faced past a perfectly competitive house is perfectly elastic or flat, considering the perfectly competitive firm tin can sell whatever quantity it wishes at the prevailing market price. In dissimilarity, the demand curve, as faced by a monopolist, is the marketplace demand curve, since a monopolist is the but firm in the market, and hence is downward sloping.

The demand curve equally faced by a monopolistic competitor is non flat, but rather downward-sloping, which means that the monopolistic competitor can enhance its price without losing all of its customers or lower the price and gain more than customers. Since in that location are substitutes, the need curve facing a monopolistically competitive firm is more elastic than that of a monopoly where there are no close substitutes. If a monopolist raises its toll, some consumers will choose not to purchase its product—merely they will and so need to purchase a completely different product. Even so, when a monopolistic competitor raises its cost, some consumers will choose not to purchase the production at all, but others will cull to purchase a like product from another firm. If a monopolistic competitor raises its price, it will not lose every bit many customers as would a perfectly competitive firm, but information technology will lose more customers than would a monopoly that raised its prices.

At a glance, the need curves faced by a monopoly and by a monopolistic competitor look similar—that is, they both gradient down. But the underlying economic meaning of these perceived demand curves is dissimilar, because a monopolist faces the market need bend and a monopolistic competitor does not. Rather, a monopolistically competitive firm'south need bend is but i of many firms that make up the "before" market demand curve. Are you lot following? If then, how would you categorize the market for golf balls? Accept a swing, and so see the following Clear It Upward feature.

Are golf balls really differentiated products?

Monopolistic competition refers to an manufacture that has more than a few firms, each offer a product which, from the consumer'due south perspective, is different from its competitors. The U.S. Golf game Association runs a laboratory that tests 20,000 golf balls a yr. There are strict rules for what makes a golf ball legal. The weight of a golf ball cannot exceed 1.620 ounces and its bore cannot be less than ane.680 inches (which is a weight of 45.93 grams and a bore of 42.67 millimeters, in case you were wondering). The assurance are also tested by beingness striking at different speeds. For example, the distance test involves having a mechanical golfer hit the ball with a titanium commuter and a swing speed of 120 miles per hour. As the testing middle explains: "The USGA system and then uses an array of sensors that accurately measure the flying of a golf brawl during a short, indoor trajectory from a brawl launcher. From this flight information, a computer calculates the elevator and drag forces that are generated by the speed, spin, and dimple pattern of the brawl. … The altitude limit is 317 yards."

Over 1800 golf game balls made by more 100 companies meet the USGA standards. The balls practice differ in various ways, like the pattern of dimples on the ball, the types of plastic used on the cover and in the cores, and so on. Since all balls need to conform to the USGA tests, they are much more alike than different. In other words, golf ball manufacturers are monopolistically competitive.

However, retail sales of golf balls are about $500 million per year, which means that a lot of large companies have a powerful incentive to persuade players that golf balls are highly differentiated and that information technology makes a huge difference which one you choose. Sure, Tiger Wood can tell the deviation. For the average duffer (golf game-speak for a "mediocre player") who plays a few times a summer—and who loses a lot of golf balls to the forest and lake and needs to buy new ones—most golf assurance are pretty much duplicate.

How a Monopolistic Competitor Chooses Price and Quantity

The monopolistically competitive firm decides on its profit-maximizing quantity and price in much the same way as a monopolist. A monopolistic competitor, like a monopolist, faces a down-sloping need curve, and and then information technology will choose some combination of price and quantity along its perceived need curve.

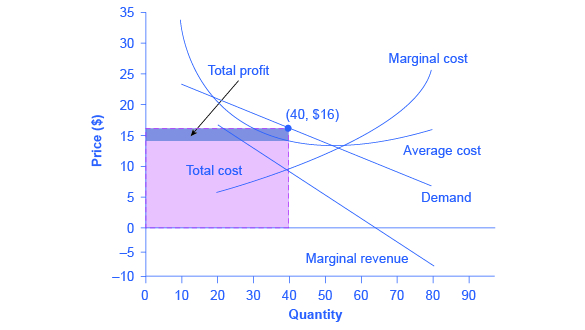

As an example of a profit-maximizing monopolistic competitor, consider the Authentic Chinese Pizza store, which serves pizza with cheese, sweet and sour sauce, and your option of vegetables and meats. Although Accurate Chinese Pizza must compete against other pizza businesses and restaurants, it has a differentiated product. The firm's perceived demand curve is downward sloping, every bit shown in Figure ii and the first two columns of Table i.

| Quantity | Toll | Total Acquirement | Marginal Revenue | Full Cost | Marginal Cost | Average Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | $23 | $230 | – | $340 | – | $34 |

| 20 | $20 | $400 | $17 | $400 | $6 | $twenty |

| thirty | $18 | $540 | $14 | $480 | $8 | $16 |

| 40 | $16 | $640 | $10 | $580 | $10 | $14.l |

| l | $fourteen | $700 | $half dozen | $700 | $12 | $14 |

| 60 | $12 | $720 | $two | $840 | $14 | $14 |

| 70 | $ten | $700 | –$two | $i,020 | $xviii | $14.57 |

| 80 | $8 | $640 | –$6 | $1,280 | $26 | $sixteen |

| Table 1. Revenue and Cost Schedule | ||||||

The combinations of price and quantity at each point on the need curve can be multiplied to calculate the total acquirement that the house would receive, which is shown in the tertiary column of Tabular array i. The fourth column, marginal revenue, is calculated every bit the change in full revenue divided by the change in quantity. The terminal columns of Tabular array one show total toll, marginal cost, and average toll. Equally always, marginal cost is calculated past dividing the alter in total toll past the alter in quantity, while average cost is calculated by dividing full cost by quantity. The following Work It Out feature shows how these firms summate how much of its production to supply at what price.

How a Monopolistic Competitor Determines How Much to Produce and at What Price

The process past which a monopolistic competitor chooses its profit-maximizing quantity and price resembles closely how a monopoly makes these decisions process. Kickoff, the firm selects the profit-maximizing quantity to produce. Then the firm decides what price to charge for that quantity.

Step ane. The monopolistic competitor determines its profit-maximizing level of output. In this case, the Authentic Chinese Pizza visitor will decide the turn a profit-maximizing quantity to produce by because its marginal revenues and marginal costs. 2 scenarios are possible:

- If the firm is producing at a quantity of output where marginal revenue exceeds marginal price, then the business firm should keep expanding production, because each marginal unit of measurement is adding to profit by bringing in more revenue than its price. In this manner, the house will produce up to the quantity where MR = MC.

- If the house is producing at a quantity where marginal costs exceed marginal revenue, then each marginal unit of measurement is costing more than the revenue information technology brings in, and the business firm will increment its profits past reducing the quantity of output until MR = MC.

In this case, MR and MC intersect at a quantity of 40, which is the profit-maximizing level of output for the firm.

Step two. The monopolistic competitor decides what price to charge. When the firm has adamant its profit-maximizing quantity of output, information technology can and then look to its perceived demand bend to observe out what it can accuse for that quantity of output. On the graph, this process can be shown as a vertical line reaching upwardly through the turn a profit-maximizing quantity until it hits the firm's perceived demand curve. For Accurate Chinese Pizza, information technology should charge a toll of $sixteen per pizza for a quantity of 40.

Once the firm has chosen toll and quantity, it'southward in a position to summate full revenue, total cost, and profit. At a quantity of 40, the cost of $sixteen lies to a higher place the average cost curve, so the house is making economic profits. From Table one we can meet that, at an output of twoscore, the business firm's total acquirement is $640 and its total cost is $580, so profits are $threescore. In Effigy 2, the firm'south total revenues are the rectangle with the quantity of 40 on the horizontal axis and the price of $xvi on the vertical axis. The firm'southward total costs are the light shaded rectangle with the same quantity of 40 on the horizontal axis but the boilerplate price of $14.l on the vertical axis. Profits are total revenues minus total costs, which is the shaded area above the average cost curve.

Although the process by which a monopolistic competitor makes decisions nigh quantity and price is similar to the way in which a monopolist makes such decisions, two differences are worth remembering. Showtime, although both a monopolist and a monopolistic competitor confront downward-sloping demand curves, the monopolist's perceived demand bend is the market need curve, while the perceived demand bend for a monopolistic competitor is based on the extent of its product differentiation and how many competitors it faces. 2d, a monopolist is surrounded by barriers to entry and need not fear entry, but a monopolistic competitor who earns profits must expect the entry of firms with similar, but differentiated, products.

Monopolistic Competitors and Entry

If one monopolistic competitor earns positive economic profits, other firms will be tempted to enter the market. A gas station with a corking location must worry that other gas stations might open across the street or down the route—and possibly the new gas stations will sell coffee or have a carwash or another attraction to lure customers. A successful eatery with a unique barbecue sauce must be concerned that other restaurants will try to copy the sauce or offer their own unique recipes. A laundry detergent with a peachy reputation for quality must exist concerned that other competitors may seek to build their own reputations.

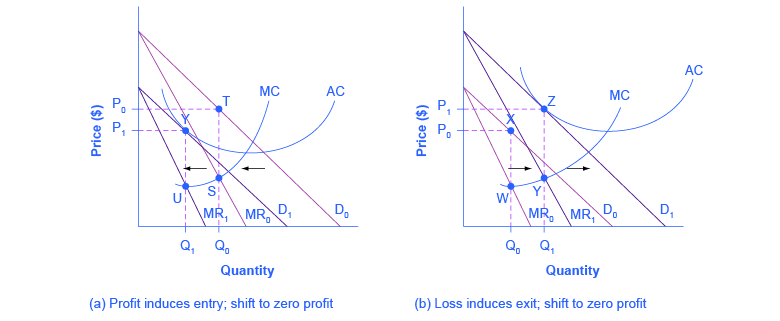

The entry of other firms into the same general market (like gas, restaurants, or detergent) shifts the demand bend faced by a monopolistically competitive house. Every bit more firms enter the marketplace, the quantity demanded at a given cost for whatever particular firm will decline, and the firm's perceived demand curve will shift to the left. Equally a house's perceived need curve shifts to the left, its marginal revenue curve will shift to the left, also. The shift in marginal acquirement will change the profit-maximizing quantity that the business firm chooses to produce, since marginal acquirement will and then equal marginal cost at a lower quantity.

Figure three (a) shows a situation in which a monopolistic competitor was earning a profit with its original perceived demand bend (D0). The intersection of the marginal revenue curve (MR0) and marginal cost bend (MC) occurs at point S, respective to quantity Q0, which is associated on the demand bend at bespeak T with price P0. The combination of price P0 and quantity Q0 lies above the boilerplate cost curve, which shows that the firm is earning positive economic profits.

Unlike a monopoly, with its high barriers to entry, a monopolistically competitive business firm with positive economic profits will attract competition. When another competitor enters the marketplace, the original firm'south perceived demand bend shifts to the left, from D0 to D1, and the associated marginal acquirement curve shifts from MR0 to MR1. The new profit-maximizing output is Qi, because the intersection of the MR1 and MC now occurs at point U. Moving vertically up from that quantity on the new demand bend, the optimal toll is at Pone.

As long as the house is earning positive economic profits, new competitors will continue to enter the market, reducing the original firm's demand and marginal revenue curves. The long-run equilibrium is shown in the figure at point Y, where the house's perceived need curve touches the boilerplate cost curve. When price is equal to boilerplate toll, economic profits are zero. Thus, although a monopolistically competitive firm may earn positive economical profits in the short term, the process of new entry will drive down economic profits to zero in the long run. Remember that zero economic profit is not equivalent to zip accounting profit. A zero economic profit means the firm's accounting profit is equal to what its resources could earn in their next best utilize. Figure 3 (b) shows the reverse situation, where a monopolistically competitive firm is originally losing money. The adjustment to long-run equilibrium is analogous to the previous case. The economic losses pb to firms exiting, which volition event in increased need for this item business firm, and consequently lower losses. Firms exit up to the signal where in that location are no more losses in this market, for case when the demand curve touches the average cost curve, as in point Z.

Monopolistic competitors can make an economical profit or loss in the short run, merely in the long run, entry and go out will drive these firms toward a zip economical profit effect. However, the zero economical profit outcome in monopolistic competition looks different from the zero economical turn a profit outcome in perfect competition in several ways relating both to efficiency and to variety in the market.

Monopolistic Competition and Efficiency

The long-term upshot of entry and exit in a perfectly competitive market is that all firms end up selling at the toll level adamant by the lowest point on the average cost bend. This outcome is why perfect contest displays productive efficiency: goods are being produced at the lowest possible average cost. However, in monopolistic contest, the end outcome of entry and exit is that firms cease up with a price that lies on the downward-sloping portion of the average cost curve, not at the very bottom of the Air conditioning bend. Thus, monopolistic competition will not be productively efficient.

In a perfectly competitive market place, each firm produces at a quantity where price is set equal to marginal price, both in the brusk run and in the long run. This outcome is why perfect competition displays allocative efficiency: the social benefits of additional production, as measured by the marginal benefit, which is the same equally the price, equal the marginal costs to society of that production. In a monopolistically competitive market, the dominion for maximizing profit is to prepare MR = MC—and price is higher than marginal revenue, not equal to it because the need curve is downward sloping. When P > MC, which is the outcome in a monopolistically competitive market place, the benefits to society of providing additional quantity, as measured past the price that people are willing to pay, exceed the marginal costs to lodge of producing those units. A monopolistically competitive firm does not produce more, which means that society loses the net benefit of those extra units. This is the same argument we fabricated about monopoly, but in this case to a lesser caste. Thus, a monopolistically competitive manufacture volition produce a lower quantity of a practiced and charge a higher price for it than would a perfectly competitive industry. See the following Clear Information technology Up feature for more item on the impact of demand shifts.

Why does a shift in perceived demand cause a shift in marginal acquirement?

The combinations of cost and quantity at each point on a business firm's perceived need bend are used to calculate total revenue for each combination of price and quantity. This information on total revenue is so used to calculate marginal revenue, which is the modify in total revenue divided by the change in quantity. A change in perceived demand will change total revenue at every quantity of output and in turn, the alter in total revenue will shift marginal revenue at each quantity of output. Thus, when entry occurs in a monopolistically competitive industry, the perceived demand curve for each house will shift to the left, because a smaller quantity will be demanded at any given price. Another manner of interpreting this shift in demand is to notice that, for each quantity sold, a lower price will exist charged. Consequently, the marginal acquirement volition be lower for each quantity sold—and the marginal revenue curve volition shift to the left equally well. Conversely, exit causes the perceived demand curve for a monopolistically competitive house to shift to the right and the corresponding marginal revenue bend to shift correct, too.

A monopolistically competitive industry does not display productive and allocative efficiency in either the short run, when firms are making economical profits and losses, nor in the long run, when firms are earning cypher profits.

The Benefits of Variety and Product Differentiation

Even though monopolistic competition does not provide productive efficiency or allocative efficiency, it does accept benefits of its ain. Product differentiation is based on variety and innovation. Many people would prefer to live in an economy with many kinds of wearing apparel, foods, and car styles; not in a world of perfect competition where anybody will always wear blue jeans and white shirts, swallow only spaghetti with plain ruddy sauce, and drive an identical model of auto. Many people would adopt to live in an economic system where firms are struggling to effigy out ways of attracting customers by methods like friendlier service, complimentary delivery, guarantees of quality, variations on existing products, and a better shopping experience.

Economists take struggled, with only partial success, to address the question of whether a marketplace-oriented economy produces the optimal amount of multifariousness. Critics of marketplace-oriented economies argue that social club does not really need dozens of different athletic shoes or breakfast cereals or automobiles. They argue that much of the cost of creating such a high degree of product differentiation, and so of advertising and marketing this differentiation, is socially wasteful—that is, most people would be just as happy with a smaller range of differentiated products produced and sold at a lower price. Defenders of a market-oriented economy respond that if people do not desire to purchase differentiated products or highly advertised brand names, no one is forcing them to do so. Moreover, they argue that consumers benefit substantially when firms seek short-term profits by providing differentiated products. This controversy may never be fully resolved, in office because deciding on the optimal corporeality of variety is very hard, and in part because the 2 sides often place different values on what variety means for consumers. Read the following Clear It Up characteristic for a word on the role that advertising plays in monopolistic competition.

How does advertising bear upon monopolistic contest?

The U.Southward. economy spent well-nigh $180.12 billion on advertising in 2014, according to eMarketer.com. Roughly one tertiary of this was idiot box ad, and some other third was divided roughly equally between Cyberspace, newspapers, and radio. The remaining third was divided up between direct mail, magazines, telephone directory yellow pages, and billboards. Mobile devices are increasing the opportunities for advertisers.

Advertizing is all near explaining to people, or making people believe, that the products of one firm are differentiated from the products of another firm. In the framework of monopolistic competition, at that place are two means to conceive of how advertising works: either advertising causes a house's perceived demand curve to become more than inelastic (that is, it causes the perceived demand bend to get steeper); or advertising causes demand for the firm's product to increase (that is, information technology causes the house'due south perceived demand curve to shift to the correct). In either example, a successful advertising campaign may permit a firm to sell either a greater quantity or to charge a higher cost, or both, and thus increase its profits.

However, economists and concern owners have also long suspected that much of the advertising may only offset other advert. Economist A. C. Pigou wrote the following back in 1920 in his book, The Economic science of Welfare:

It may happen that expenditures on advertising made by competing monopolists [that is, what nosotros at present call monopolistic competitors] will simply neutralise 1 some other, and leave the industrial position exactly equally it would have been if neither had expended anything. For, clearly, if each of two rivals makes equal efforts to attract the favour of the public away from the other, the total result is the same as it would accept been if neither had made any effort at all.

Central Concepts and Summary

Monopolistic competition refers to a market where many firms sell differentiated products. Differentiated products can arise from characteristics of the practiced or service, location from which the product is sold, intangible aspects of the product, and perceptions of the product.

The perceived need curve for a monopolistically competitive firm is downward-sloping, which shows that it is a price maker and chooses a combination of price and quantity. However, the perceived demand bend for a monopolistic competitor is more elastic than the perceived demand curve for a monopolist, because the monopolistic competitor has direct contest, unlike the pure monopolist. A profit-maximizing monopolistic competitor will seek out the quantity where marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost. The monopolistic competitor will produce that level of output and accuse the price that is indicated by the firm's demand curve.

If the firms in a monopolistically competitive manufacture are earning economical profits, the industry will attract entry until profits are driven down to nada in the long run. If the firms in a monopolistically competitive industry are suffering economic losses, then the industry will experience exit of firms until economic profits are driven upwardly to cypher in the long run.

A monopolistically competitive firm is not productively efficient because it does not produce at the minimum of its average cost curve. A monopolistically competitive firm is not allocatively efficient because it does non produce where P = MC, merely instead produces where P > MC. Thus, a monopolistically competitive firm volition tend to produce a lower quantity at a higher cost and to accuse a higher cost than a perfectly competitive business firm.

Monopolistically competitive industries do offering benefits to consumers in the form of greater diversity and incentives for improved products and services. There is some controversy over whether a market-oriented economy generates too much variety.

Self-Check Questions

- Suppose that, due to a successful advertizing campaign, a monopolistic competitor experiences an increase in need for its production. How volition that affect the toll it charges and the quantity it supplies?

- Continuing with the scenario outlined in question 1, in the long run, the positive economical profits earned past the monopolistic competitor will attract a response either from existing firms in the industry or firms exterior. As those firms capture the original house's profit, what will happen to the original firm'south profit-maximizing price and output levels?

Review Questions

- What is the relationship between product differentiation and monopolistic contest?

- How is the perceived need curve for a monopolistically competitive firm different from the perceived demand curve for a monopoly or a perfectly competitive business firm?

- How does a monopolistic competitor choose its profit-maximizing quantity of output and cost?

- How can a monopolistic competitor tell whether the price information technology is charging will cause the house to earn profits or feel losses?

- If the firms in a monopolistically competitive marketplace are earning economical profits or losses in the short run, would you await them to continue doing so in the long run? Why?

- Is a monopolistically competitive house productively efficient? Is information technology allocatively efficient? Why or why not?

Critical Thinking Questions

- Aside from advertising, how can monopolistically competitive firms increase demand for their products?

- Make a case for why monopolistically competitive industries never reach long-run equilibrium.

- Would y'all rather accept efficiency or variety? That is, one opportunity cost of the variety of products we accept is that each product costs more per unit than if in that location were only ane kind of product of a given type, like shoes. Peradventure a improve question is, "What is the right amount of variety? Can there be too many varieties of shoes, for example?"

Problems

Andrea's Twenty-four hour period Spa began to offering a relaxing aromatherapy handling. The business firm asks yous how much to charge to maximize profits. The demand curve for the treatments is given by the first two columns in Table two; its total costs are given in the third column. For each level of output, calculate full acquirement, marginal revenue, average price, and marginal cost. What is the profit-maximizing level of output for the treatments and how much will the firm earn in profits?

| Toll | Quantity | TC |

|---|---|---|

| $25.00 | 0 | $130 |

| $24.00 | 10 | $275 |

| $23.00 | 20 | $435 |

| $22.50 | thirty | $610 |

| $22.00 | xl | $800 |

| $21.threescore | 50 | $one,005 |

| $21.20 | 60 | $1,225 |

| Table 2. | ||

References

Kantar Media. "Our Insights: Infographic—U.Southward. Ad Year Cease Trends Report 2012." Accessed October 17, 2013. http://kantarmedia.united states of america/insight-middle/reports/infographic-us-advertising-year-cease-trends-report-2012.

Statistica.com. 2015. "Number of Restaurants in the United States from 2011 to 2014." Accessed March 27, 2015. http://www.statista.com/statistics/244616/number-of-qsr-fsr-chain-independent-restaurants-in-the-us/.

Glossary

- differentiated product

- a product that is perceived past consumers as distinctive in some way

- imperfectly competitive

- firms and organizations that fall between the extremes of monopoly and perfect competition

- monopolistic contest

- many firms competing to sell like but differentiated products

- oligopoly

- when a few large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry

Solutions

Answers to Cocky-Check Questions

- An increment in need will manifest itself every bit a rightward shift in the demand curve, and a rightward shift in marginal revenue. The shift in marginal revenue will cause a motion up the marginal toll curve to the new intersection between MR and MC at a higher level of output. The new toll tin be read by cartoon a line upwards from the new output level to the new demand bend, and so over to the vertical axis. The new price should be higher. The increase in quantity will cause a movement forth the average cost bend to a peradventure college level of average cost. The price, though, volition increase more than, causing an increase in full profits.

- As long as the original firm is earning positive economic profits, other firms will respond in ways that accept away the original business firm's profits. This will manifest itself as a decrease in need for the original firm's product, a decrease in the firm'southward profit-maximizing cost and a subtract in the firm's profit-maximizing level of output, essentially unwinding the process described in the respond to question 1. In the long-run equilibrium, all firms in monopolistically competitive markets volition earn zero economical profits.

hedlundmicketionath.blogspot.com

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/principlesofeconomics/chapter/10-1-monopolistic-competition/

0 Response to "in what industries would you expect to see efficiency wages?"

Post a Comment